Bedfellows Blankets founder Peggy Hart with good friend and textile mill afficionado, Leonard Brodt

Story and images by Fibershed intern Charlotte Atkinson

Tucked away in the tiny town of Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts sits an impressive collection of machinery left from New England’s Industrial Revolution. Bedfellow Blankets’ Peggy Hart has been the proud owner of a piece of that time with her 1920’s-1940’s era Crompton & Knowles W-3 power looms since she purchased them with the help of her dear friend Leonard Brodt in 1982.

It was a huge endeavor to get the looms running again as they weren’t exactly in good shape when they were purchased. Peggy says she even recalls a shuttle flying across the room on some occasions and parts for the looms were extremely difficult to find. The project would not have been made possible without Lenny’s expertise, as he had spent his whole life working in the New England textile mills in the early 1940s starting at the age of 16. Peggy says that she always had a passion for fiber arts, and as a hand spinner and weaver, she enjoyed the process from sheep to finished product. She currently works with sheep farmers weaving blankets for them with their own yarn, and has made a few blankets for projects with the Columbus Museum, CESA (community involved in sustaining agriculture), and a reproduction blanket for the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

I caught up with Peggy recently to learn about the past and present textile industry landscape in New England and models that are working (as well as work that needs to be be done). Here’s what she had to say:

To start off, I’d love to know more about you and how you became involved in the fiber arts and wool industries?

PEGGY: Well I started as a hand weaver back when I was much younger. After college I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya, and I started a spinning and weaving workshop there. I really liked doing production but I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to do production when I went back to the States and be able to sell it because handwork was just so labor intensive. I went to visit a woman named Deborah Abbot who had some looms just like these in a barn in New Hampshire. At the time she was making women’s coating fabrics, she was sewing it up and selling them. I thought well if she can run these looms in a barn, then I could do that. So I went to RISD and took all of the industrial classes that I could. Then I got out of RISD and went to work at Worcester Textile, a mill that was still weaving wool in Rhode Island. After that, Lenny and I bought the looms, and I set them up and started weaving. Worcester Textile was in North Providence, and they were the last mill running as far as I know in Rhode Island. When Lenny and I bought these looms, for years we scavenged for parts from all over, especially in Rhode Island because you know they hadn’t been making these looms for around 40 years. This was in the mid 1980s, so parts were scarce. Lenny really knew that we could never keep them running unless we had parts, so we started collecting them. Upstairs in the milk stalls it’s this glory hall of loom parts.

Can you tell me about each piece of equipment and the history behind them?

PEGGY: Crompton & Knowles Loom Works was a company in Worcester, Massachusetts and it was started by two men who were both working on loom design from the 1840s onward. Crompton invented the first fancy power loom, and this other guy Knowles was also working on loom design and started a little bit later. He was also in Worcester, and they were competitors for many years until they finally merged in 1897 and started making looms together. There is a million different things that go into making a loom run well, or even for it to just do its basic functions. Both of them were really good at figuring out different ways of doing pattern with metal pattern chains. The other thing was the box motion, and the way that you could run more than one color in a piece of fabric which was really important for things like plaids. Both men took out hundreds of patents for all aspects of that. Crompton & Knowles as a company had a whole division of people that were working on patents and innovations. I think the company had something like 2,000 patents eventually, but they weren’t for full fledged looms they were for minor tweaks. They also made cotton looms, silk looms, carpet looms, felt looms; they had quite a variety. None of those are still in existence because they pretty much all went for scrap.

There were such radical changes in the way that looms worked because they are completely mechanical with not a single computer or electronic part in them at all. As loom technology changed, these became obsolete really fast and sold for scrap metal. Even museums like the American Textile History Museum in Lowell, MA closed. They had some of these looms and they actually ran them in the early years of the museum, but those looms all got dispersed and some of them are in North Carolina now, and a lot of them went overseas. The thing about them is that they are pretty straight forward in many ways in how they work, because they are mechanical so a lot of them went overseas to developing countries where they are still running.

I understand that much of the equipment from this time period has been destroyed, how hard was it for you to acquire these looms?

LENNY: In those days it was tough because mills had their looms and their machinery and they just kept going and going. They never sold them until they began to lose business. When they couldn’t produce and couldn’t make money, they would sell the looms and close the mills down.

PEGGY: By the mid 80s a lot of woolen mills were already shut, but there were still some going. So these two looms we got from a mill that was using them, but they had just upgraded to shuttleless looms so they were willing to sell us these.

LENNY: Of course they had problems too, when we got them they needed work. At one point we had a shuttle come flying out.

PEGGY: Lenny restored them like getting an old car and getting it perfect. I don’t run them like you would 40 hours per week in a mill, and so you know they are holding up really well. Around that time we were scavenging parts, we were going to all these old mills that had closed and throwing parts in the trunk of Lenny’s car. What car was that? Was it a Buick or something?

LENNY: Oh was it blue? Pontiac?

PEGGY: Yea! That’s what it was. Anyway, you could fit an enormous amount of stuff in the trunk!

LENNY: I used to put big metal beams in my truck.

PEGGY: And you know, if you looked at the car from the side, it would be riding really low in the back!

LENNY: Well I didn’t care, I was a textile man!

PEGGY: So eventually all of that stuff made its way upstairs.

LENNY: There were times when Peggy needed a part, and we were very scared about where to get it.

PEGGY: There were mills that were still running, and Lenny had worked at all of them. He knew everybody that had been involved.

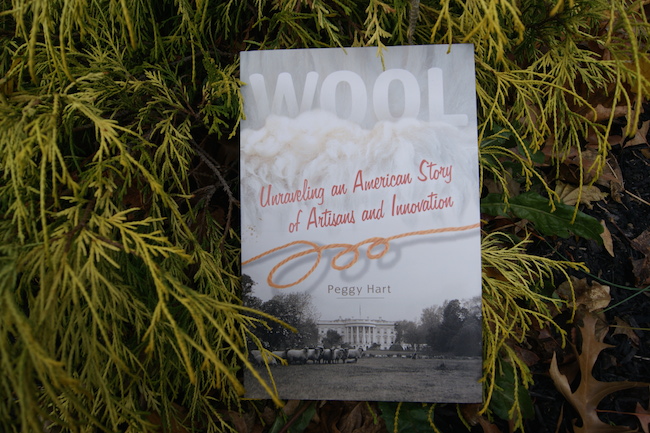

I am excited to see that you’ve written a book titled Wool, Unraveling an American Story of Artisans and Innovation. Can you tell me more about it?

PEGGY: It’s four centuries of production and consumption of wool in the United States, which is a hopelessly broad topic. In the process of writing the book I realized that the main story that I was really telling was about consumption. I was trying to track per capita the consumption of wool over the centuries, and why people wore wool starting in the 17th century and up until what people are wearing for wool now. I used a lot of census data to try and nail down those statistics, but what I found was that there was this change from wearing wool in New England simply because you had to, to people wearing it all over the country because it became more available with industrialization. Still because they had to, but then there was this big shift after the beginning of the 20th century with things like indoor heating, washing machines, people driving in cars instead of walking where they would need to have something to keep them warm. I finally ended with hoping that I could make the case for people continuing to use wool, that it was a wonderful fiber that it’s of course sustainable and really functional.”

Is there a growing need for small scale artisan weavers? Who are your typical clients?

PEGGY: What I’m doing is custom work and custom weaving. It’s really a pain to do custom work, especially when yarn is less available than it used to be. So what I have fallen into is the sheep farming thing. I’m kind of like the only game in the country as far as somebody that has a loom that’s wide enough to weave blankets on and a shuttle loom, because in order to make blankets you want to have woven selvedges. So that’s what these looms are great for. There could be a growing need if there was more interest in having local fabric woven. There’s a guy out in California that’s weaving for the California Fibershed, I think his name is Ryan Huston of Huston Textiles. Actually he came out here to get parts from me. He got into it like 35 years after I did, and by that point it was extremely hard to find these old looms. He’s got some shuttleless looms, but he also found out about somebody that had squirrelled away some of these looms in her garage in Connecticut. So he came all the way from California and bought them, just because they were the only things that were still left and the house was getting sold and the garage had to be emptied. He bought them and then came here for some parts. It would be lovely if there was more demand for custom work like that.

Lenny, you have spent your whole life in the textile industry here in New England, what was it like for you living through that time?

LENNY: My father was a loom fixer in textiles and therefore I was too. I was 16 I think before World War II, I was born in 1926. The war was going on in Europe before we got involved, but yea, early 1940s. The Industrial Revolution was the textile industry which kept America afloat, until it faded away when the industry moved overseas. My first job was learning how to weave, and I was set up with Frank Cazeba, a weaver who taught me. After I got used to it, I was given four looms to run and I ran them for some time. I left the textile industry to go into the service in WWII, a lot of men back then went into the service. When I came back I went back to weaving, and then I worked my way into loom fixing. I used to watch the looms, I’d pay attention to how they’d operate when I was weaving, and I got friendly with some of the stuff, so then I decided to try loom fixing. Loom fixing is a mechanical trade, if you’re good at mechanics you could get into it, but there was a lot of people who were not mechanically inclined, so they had difficulty. I slipped right into it and I enjoyed it and spent my whole life doing it. There were times when I was fixing looms and I was the boss of the weave shop at the same time. Didn’t do me any good, only a few bucks a year you know. I retired at 62 years old, but even though I retired I kept working. Not that I wanted to make money, I don’t want to make money because if you make money you have to pay income tax, and if you don’t make any money you don’t have to pay income tax. So therefore, I worked but I didn’t want to make any money, but I did keep my bread on the table. I survived and that’s all I wanted anyway. Getting rich isn’t the best thing in the world, I kept myself busy. I had good ideas, but when time gets a grip on you it won’t let go. You know, when you grow old, old age is like a grip that you can’t get out of because growing old is a one way street; you can’t get younger! You find that out as you progress in life. I always enjoyed textiles, I always enjoyed working and I still like to work but I’m too old to keep going. I’m dying on my feet, I’m 92 ½ years old!

Do you see a resurgence of interest in locally produced natural fiber products? If so, do you think New England has enough resources for it to be a sustainable industry?

PEGGY: I think so, it would be a total shifting of gears. Linen could be grown here, and certainly wool is grown here. The resurgence though is really small scale at this point and I think it’s only going to get bigger if people really examine their choices. And, it would obviously mostly be natural fibers, we haven’t even talked about man made fibers. There’s certainly good reasons to use man made fibers and there have been companies in New England that have done really well with that. You know, polar fleece really works for a lot of people and I’m not going to say that nobody should wear polar fleece!

Textile manufacturing in New England has nearly vanished with overseas competition, how do you hope to see this industry revitalized again?

PEGGY: It’s going to have to be because people choose to wear locally produced fabric. That’s really the only way that it could come back. Because as long as people are just buying clothes based on their pocketbook, they are going to be buying it from Walmart instead of buying it locally produced. It’s going to have to be a shift in perceptions, and people being willing to spend more money for their clothes. To go back to the idea that they will buy clothes as an investment and wear them for longer than they typically do right now. At the same time, the industry is never going to be what it was, there were bad things about how it was. And Lenny’s father was a loom fixer before him so he grew up in a mill town. People who worked in the mills didn’t get paid enough to really live, and they had very poor lives. So, we don’t want to bring that part of it back. It has to be a new model that supports us all.

Really enjoyed reading this article.

Really interesting article & we learnt a lot. Love their passion! Excellent questions & very well written. Thank you.

What an interesting article. We learnt a lot & love their passion. The questions were excellent & very well written. Thank you. Love wool!!