Story and images by Fibershed intern Emma Werowinski

In history class I was taught that the textiles industry in New England was dead.

Two years ago, as a junior studying textiles at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), I was frustrated by how little I had learned about the textile manufacturing process, and how little I could discover from doing research online. In one class, a professor showed us YouTube videos of antique textile machinery. I was fascinated by the clanking of the machines, by their age and by the fact that even with immense technological progress in many industries, older textile machines often work better than newer ones.

So, this isn’t a sad story. I wanted to learn more, and when a final project in class didn’t provide enough research time, I designed a summer project to continue my research with funding I received through RISD.

I wanted to learn more about the current industrial capabilities of the textile industry in New England from fiber farm to finished product. I had many questions including: Is it possible to develop small to mid-scale New England made products? How much fiber does the region produce every year? What happens to old manufacturing equipment when mills go out of business? How many fibers can we grow or make in the region?

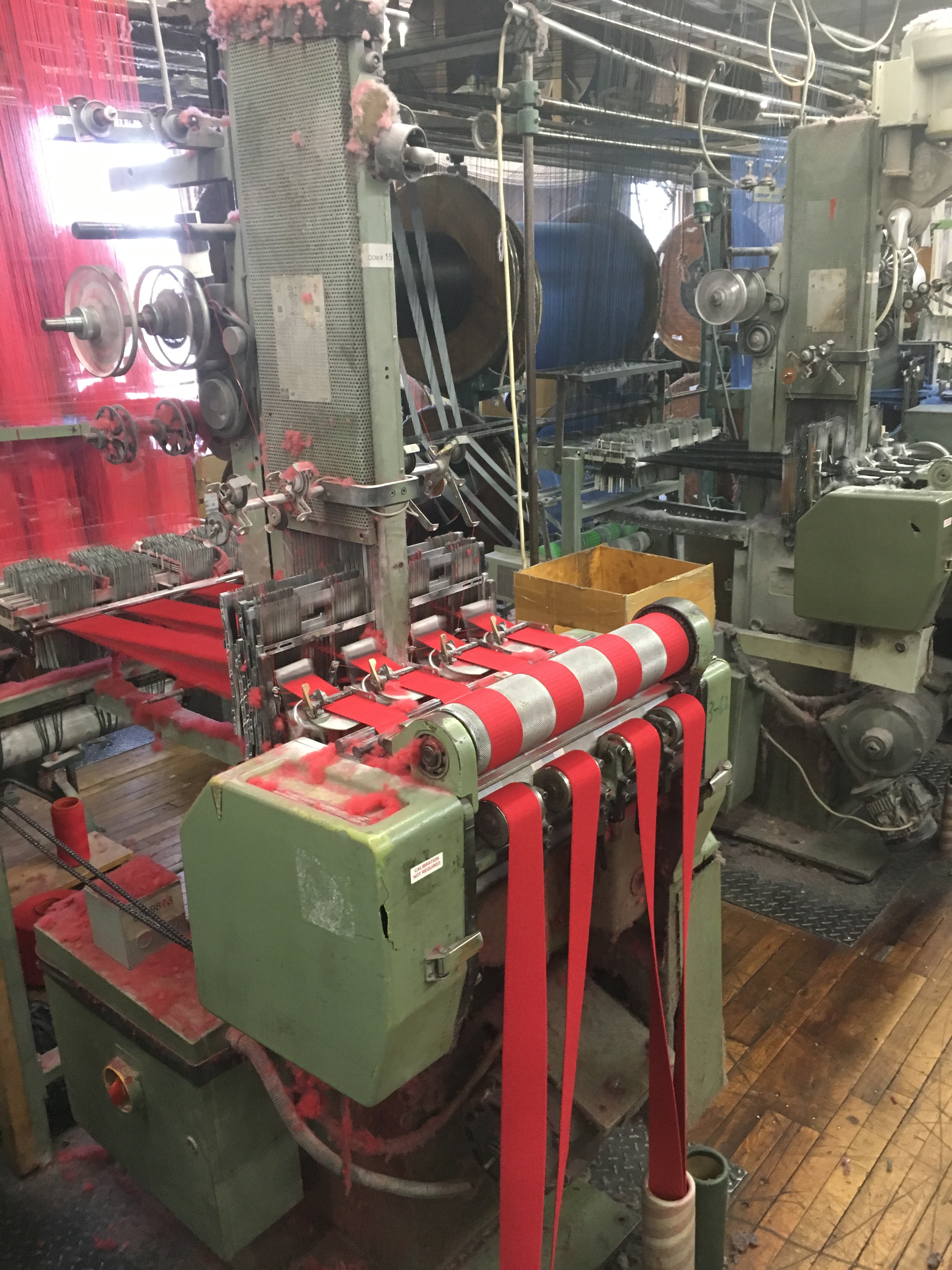

Above image and here: Image: Leedon Webbing Co., Inc. has been manufacturing narrow fabric webbing for over 70 years

We know the facts of the decline in U.S. textile production over the past 50 years. Competition from foreign imports, combined with less institutional support, manufacturing equipment sold overseas, financial crashes, and production shifting from traditionally New England based manufacturing to the Carolinas where labor was cheaper. What we don’t always know is how and why existing mills have survived and what they need to do to keep surviving.

Every day that I worked on this project turned into a new “did you know” statement:

Did you know that many mills, especially those that spin high-tech yarn and weave narrow fabric, survive off of the guaranteed business brought in by military contracts?

Image: Gowdey Reed, manufacturers of loom reeds since 1834

Did you know that more narrow woven mills have survived in New England than broadwoven mills most likely because of their ability to diversify their products from apparel into other industries like the automotive industry? (A narrow woven mill produces fabrics that are 6 inches or narrower including elastics and webbing: think the band of fabric on your underwear and dog collars).

- Did you know that the last lace mill in the United States (Leaver’s Lace) is in Rhode Island?

- Did you know how many alpaca farms there are in New England? The answer is so many. Hundreds of alpacas.

- Did you know the textile industry has its own yellow pages, called Davison’s Textile Blue Book?

Not only did I get the chance to explore an industry thriving in my own backyard, I met and worked with many others interested in the same questions.

Swan Fabrics, Fall River, MA

In class, teachers said that getting direct access to mills in the textile industry would be difficult. You would need to go through jobbers and every type of middleman you could possibly think of. I honestly thought very few people were going to respond to me, a student, asking them questions about machinery and output and reactions to industry trends and hoping to put many of those answers into an open source database. I was pleasantly surprised by the kindness I was shown by so many people who took time out of their day to talk to me and give me tours of their spaces and processes.

Over the course of my summer I visited five mills/manufacturers and learn their stories: Gowdey Reed in Central Falls, RI, Leedon Webbing in Central Falls, RI, Swan Fabrics in Fall River, MA, Matouk Luxury Linens in Fall River, MA, and Merida in Fall River, MA. The photos interspersed throughout this article come from those visits. It is also worth noting that many mills offer tours of their spaces including Jagger Brothers, a large spinning mill in Maine.

At Gowdey Reed I got the opportunity to speak in depth with the current owner. Did you know there used to be a reed maker in every mill town? Today, there are only four reed makers left in the United States. Over the years, as other reed makers in New England went out of business, Gowdey Reed purchased a lot of their equipment, which seems to be one of the major reasons why they are still in business today.

Image: Gowdey Reed

I asked the current owner what would happen when he retired. He said probably nothing. It’s hard work that he wouldn’t want anyone to have to go into. This is a common story; knowledge of certain steps in the textile process are completely lost when the people doing that work retire or pass away. It is simply not a profitable economic decision to continue working within the textiles industry in this country.

So, what’s the point of continuing textile manufacturing in the United States? I don’t have an answer for that, but I know that it’s important, and entirely possible. There are so many questions that still need to be answered and it’s going to take time and creative thinking to rebuild manufacturing models and regional supply chains that are equitable to workers, sustainable for our environment, affordable for consumers, and still profitable. But I’m excited to be a part of it, and I know my peers are too. There’s still a lot of learning left to do.

I would like to thank the following people for their advice and support throughout this project: my supervisor Jess Daniels, Fibershed, Karen Schwalbe, Southeastern Massachusetts Agricultural Partnership (SEMAP), Amy DuFault and Sarah Kelley of the Southeastern New England Fibershed, Kathleen Grevers of RISD, the RISD Textron Fellowship committee, and every single mill that took time out their busy schedules to fill out my survey, speak with me over the phone, and allow me to visit their spaces.

Wonderful work! Thank you for sharing. I wish we could support our local mills, our country’s textile industry. This is a start to getting the story out. I’m in California and there are folks trying also to tackle this same issue.